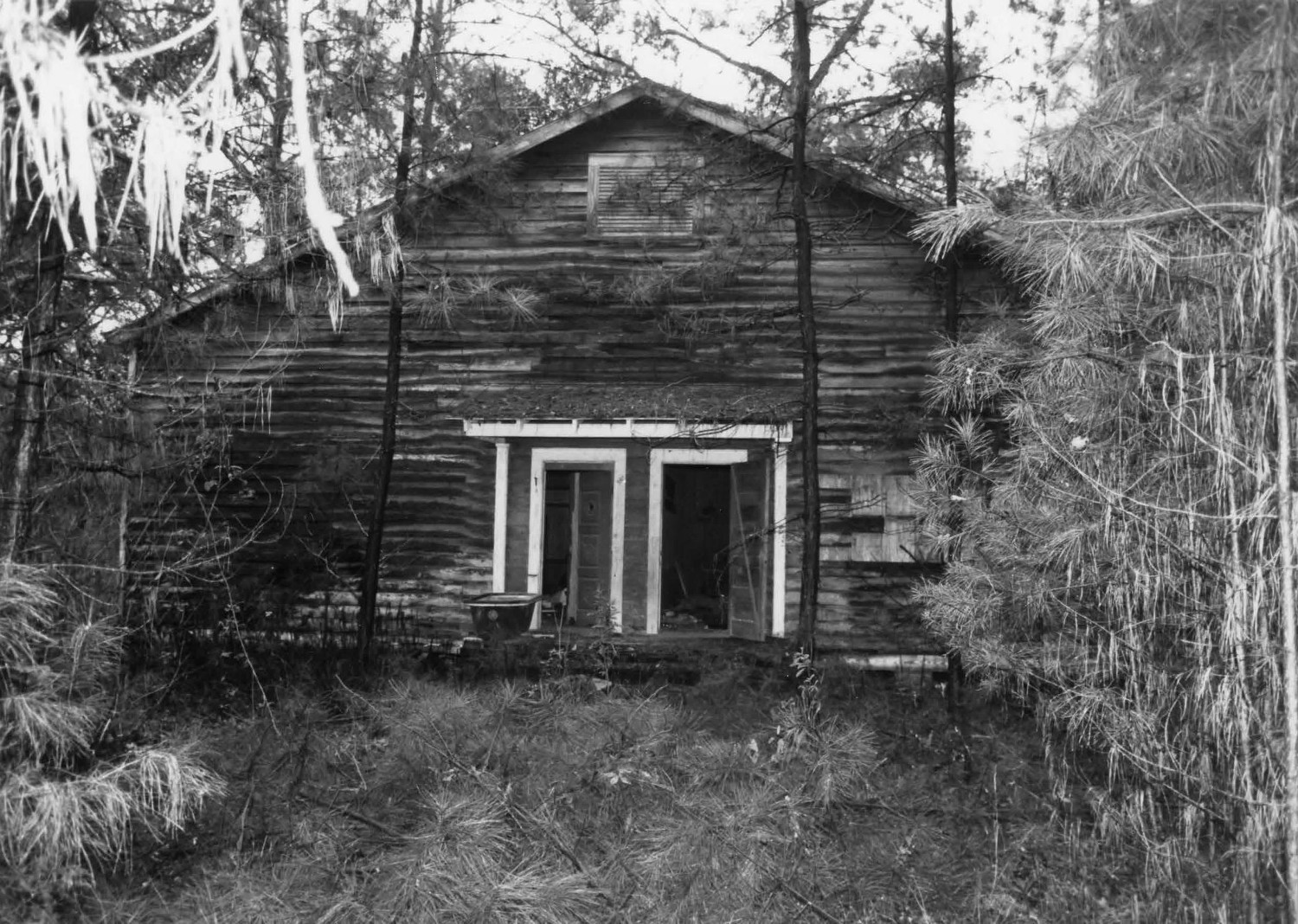

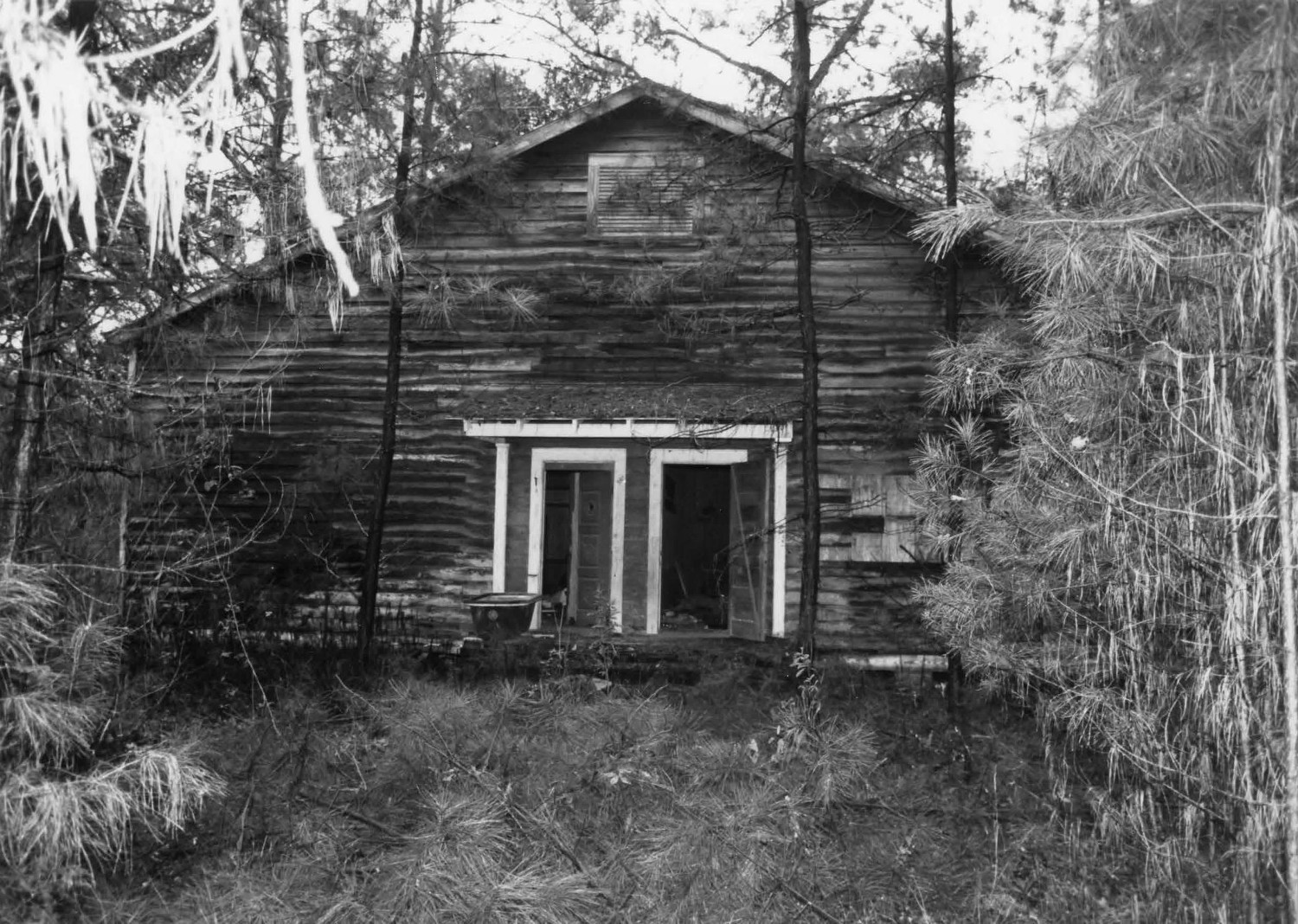

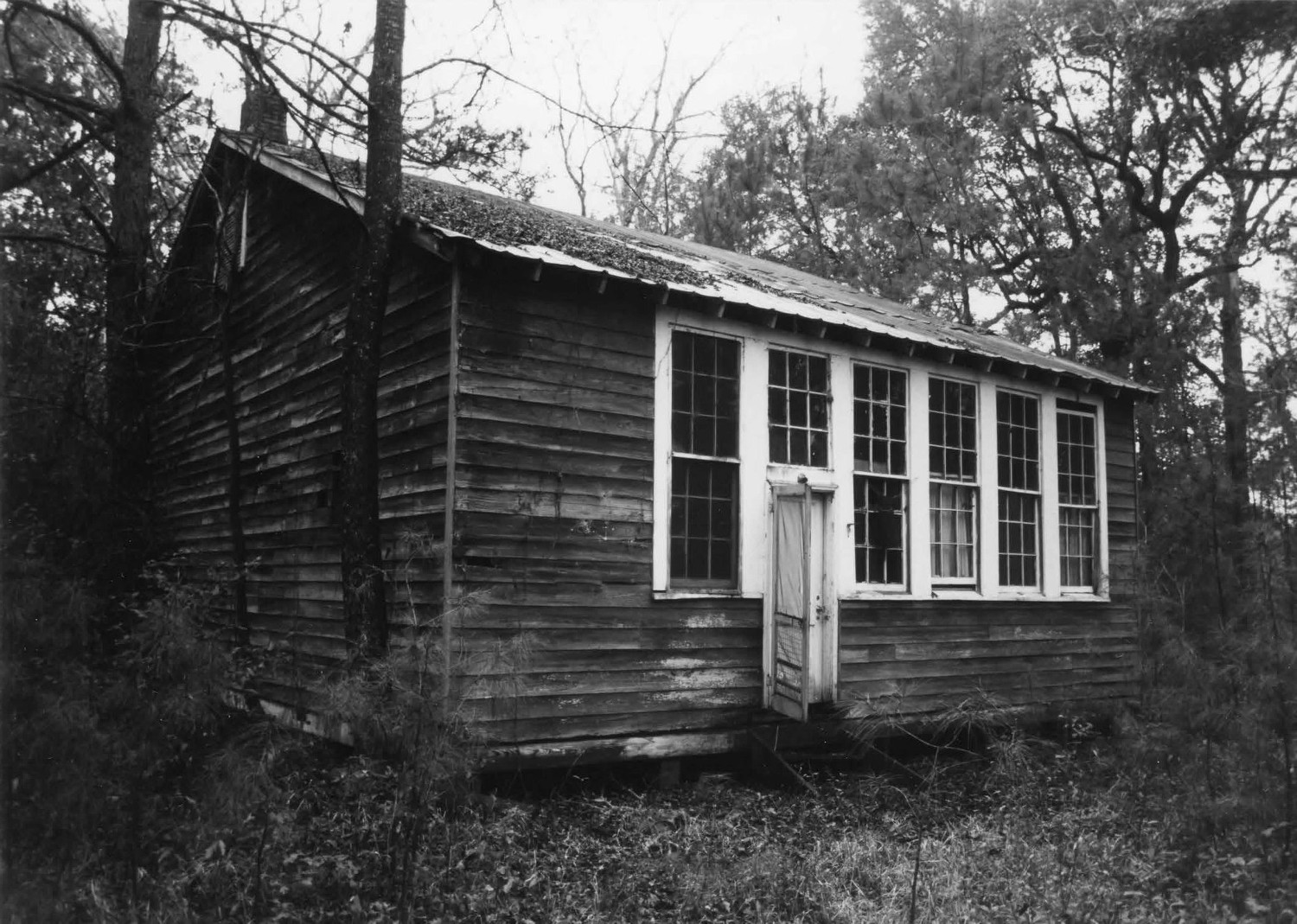

Abandoned schoolhouse in South Carolina

Seaside School, Edisto Island South Carolina

Seaside School is associated with the education of African-American Edistonians from the late-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. At least one and sometimes two school buildings have been located on its site since 1865. The present structure, built ca. 1931, is an example of a schoolhouse used by rural black South Carolinians into the 1950s. Seaside School is said by many of the older residents of Edisto Island, black and white, to be the oldest black school on the island, and is one of only three remaining historic schools on Edisto Island, of at least eight (Seaside White, Seaside Colored, Borough White, Borough Colored, Central Colored, Whaley Industrial, Edisto Island Consolidated, and Larimer Presbyterian) that have been documented on the island in the twentieth century.

The Seaside School lot was originally part of California Plantation, owned by the Mikell family of Peters Point Plantation. The Mikells and their slaves evacuated Edisto Island in the winter of 1861-62. Under General William T. Sherman's Field Order No. 15, issued in January 1865, all of South Carolina's sea islands were designated for exclusive Negro settlement, to be administered by occupying Federal troops. Several educational missionaries from the North opened schools for former slaves on Edisto Island, and before the end of 1865, Nicholas Blaisdell pre-empted California Plantation and opened a school somewhere on the property.

The Mikell family soon reclaimed California Plantation and established the adjacent Sunnyside Plantation, and the records are not clear as to when a school parcel was deeded out of California Plantation. South Carolina's postwar constitution called for free tax-supported education for all children, including those of former slaves, and Boards of Education took on the educational responsibilities of the Freedmen's Bureau. The Seaside property may have been among those that the Freedmen's Bureau gave to the associations or individuals on whose land they stood, to be used "in perpetuity" as schools for freedmen, when the Bureau ended its educational programs in 1870.

Reorganizing the free public school system was difficult, as thousands of blacks were included for the first time. Into the twentieth century, the isolation of the Sea Islands, the difficulties of transportation, and the primacy of racial segregation, resulted in white schools with tiny enrollments, while black pupils oversubscribed their own small schools. Even after South Carolina's government was returned to the Democratic Party in 1876, there was little noticeable improvement in the state's schools.

Despite the inadequacies of public education, an interesting aspect of Edisto Island's history is the substantial proportion of black children who attended school there in the 1870s and 1880s. In 1879 there were 534 "scholars" on Edisto, almost all of them black, and by the next year four schools on Edisto and Jehossee islands had 657 black pupils and seven teachers (four white, three black). Edisto Island's 3800 African-Americans were considered prosperous by their contemporaries in 1880. A system had evolved under which freedmen exchanged day labor for cash, or for the use of plots to farm on their own account. Using these rented plots, freedmen grew two-thirds of the island's cotton, while owning only about 14% of its land. Their economic well-being allowed children to go to school rather than to work.

Although it is not certain that Seaside School is a replacement for the 1865 school established by Nicholas Blaisdell, its institutional history at the present location extends at least to the 1880s. Townsend Mikell had numerous tenants and wage laborers at California and Sunnyside, and may have had reason to provide a lot for the Seaside School. White planters often experienced a serious labor shortage in areas where ex-slaves farmed their own land successfully; some therefore opposed education as being a source of black independence. Other large landowners, however, found that schools could be used as an employment benefit, to attract families to live on or near the plantation, and enter into labor agreements.

In 1880 there were four schools, with seven teachers, for 657 black pupils on Edisto Island. By contrast, there were two teachers for the 24 children in the island's single white school. Because it was not geographically accessible to the entire island, in 1881 a second white school was opened, which seems to have been located on the existing Seaside School lot. Until 1925 there were separate Seaside Schools for black and white pupils. (Board of Education Records for the years 1882-1893, when Edisto Island was transferred from Charleston to Berkeley County and back, are not complete.)

During the decade of the 1890s there was a reduction in black school attendance, and by 1899 there were only 495 pupils attending Edisto's three black schools. The reason for the decrease is not obvious, as it came before substantial outmigration of blacks from South Carolina began. It may be linked to the fact that only elementary education was available on Edisto. Beyond fifth grade, there was no place in the island's school system for black or white.

Charleston County's black high school students relied on private institutions such as Avery Institute, Shaw Memorial Institute and Wallingford Academy in the City of Charleston. Until 1910 South Carolina's only public high school for blacks was Howard in Columbia, and it was not until 1916 that Edisto's Larimer School, supported by the Presbyterian Church, U.S.A., extended its teaching to a full twelve grades.

The primary school situation on Edisto Island was consistent from before 1900 until 1925. There were three schools for blacks, Central, Borough and Seaside; the latter two shared sites, but not buildings, teachers, or libraries, with Borough White School and Seaside White School. The white student bodies remained small; the blacks remained crowded. In 1910 there were 300 students divided among the island's three schools for blacks. In 1913 Seaside Colored School's one teacher handled an average attendance of 117 in six grades.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century per-pupil expenditures in South Carolina's school districts were lower for blacks than for whites, in 1922 J. B. Felton, State Supervisor for Colored Schools, found that "only about ten percent of colored schoolhouses are respectable."

School consolidation in South Carolina began with the 1911 Rural Graded School Act was intended to provide state aid to "country communities thickly populated with white people." The number of one-teacher schools, particularly white schools, was reduced as schools were consolidated.

By the school year 1921-22, Charleston County had only 13 one-teacher schools for whites. The two white schools on Edisto Island, Seaside and Borough, were finally combined in 1925, when the Edisto Island Consolidated School was built.

The Edisto Island school district continued to operate three black schools, each with two teachers. In 1927 an average of 61 attended Borough School, with five grades; 88 attended Central, with six grades, and 93 attended Seaside, with seven grades. The Borough White School had been transferred for the use of the students of Borough Colored School, which was sold, but Seaside White School appears to have remained vacant.

In 1929 the school district trustees were authorized to "build a new colored school at Seaside site, provided the colored people there will buy and give title to four acres of land." This was not done, and in March 1930, the district was instead authorized to consolidate the Seaside and Central colored schools, and erect a four-room Rosenwald building, based on the agreement that the "colored people would raise the money for the lot and as much as they could for desks to equip the building." Coming during the Great Depression, this requirement, too, was beyond the capacity of the community. Seaside and Central were not consolidated, and the new Seaside School, built ca. 1931, is a simple two-room building, built in accordance with Clemson's Extension Service Standards of 1907 and 1917.

From 1931 until 1954, a generation of black Edistonians received their primary education in the existing Seaside School. In May 1954, St. Pauls School District #23 completed the Jane Edwards Elementary School, a consolidated school for the former pupils of Seaside, Central, Borough and Whaley Industrial schools. For the first time in nearly ninety years, Seaside School did not open for the fall term.

In 1955 the Seaside School lot, with two buildings, was conveyed to Susalee Mikell Belser, daughter of Townsend Mikell. The Belser family relocated the earlier building off the property, and began to refurbish it. Work was underway when Hurricane Gracie demolished it in 1959. The extant two-room school and privy at the Seaside School property, somewhat deteriorated but essentially unaltered since construction, are tangible reminders of educational history on Edisto Island.

Building Description

Built ca. 1931, Seaside School is a two-room frame building typical of those built throughout rural South Carolina from ca. 1910 until ca. 1940. The school, just off S.C. Highway 174, near the center of Edisto Island, faces north.

The rectangular building is one story in height, on a low brick pier foundation, with a lateral gable roof of V-crimped metal and weatherboard exterior siding. Rafter ends are exposed at the main body and at the small shed porch protecting the paired entry doors. One original five-panel door remains.

At the east and west side elevations are bands of six double-hung 6/6 wood sash windows. At the gable ends are rectangular louvered wood vents. No other openings exist at the rear elevation. A brick interior flue is centered at the rear roofline.

Seaside School has been vacant since 1954, except brief periods of residential tenant occupancy. Exterior alterations have been minor. One window at the east elevation, nearest Highway 174, has been changed to a door, one exterior door has been replaced, and the two freestanding posts have been lost from the facade porch. Two engaged posts indicate the simple character of their design.

The standards for school buildings promoted by Clemson's Extension Service between 1907 and 1917 were closely followed into the 1930s. Seaside School was built generally in accordance with these standards. The plan of each room is rectangular, with the brick chimney for the stove flue clipping the rear inside corner. A metal wood stove remains in the east classroom. Large bands of windows illuminate the classrooms; wall space not taken by windows was used for green "hyloplate" blackboards, lost in recent years. Much of the black-board trim, including the molded wood chalk tray, remains in place. The interior classrooms retain simple beaded board finishes at walls and ceilings.

A two-seat privy approximately fifty feet south of the school is severely deteriorated; it is a simple wood-frame building with roof and siding of corrugated metal and a wooden door at the east side. The simple shed roof shelters two "sanitary" toilets of poured concrete, and no evidence remains of an interior partition.

Principal (north) facade, looking south (1993)

East and south (rear) elevations, looking northwest. (1993)

Facade entry, looking south (1993)

Door detail, view from interior, looking north (1993)

Interior window detail, rear bay of east elevation, looking west (1993)